The key points of Working Effectively with Legacy Code

⛑️️ My First Aid Kit can help you rescue any codebase quickly and safely!

“Legacy Code is code without tests”

If you’ve come across that definition, it’s from Michael Feathers’ book: Working Effectively with Legacy Code.

While I have a slightly extended definition, this is a very valid and useful one!

Feathers’ book is from 2004. Yet, its content doesn’t get outdated. There is a reason for that and this CommitStrip puts it best:

This book is a reference. Probably THE reference.

When there’s a thread about Legacy Code, it doesn’t take long for someone to drop a comment suggesting you read it.

I didn’t read it. I’ve seen it’s recommended. But what are the key points of that book?

If that’s you, I got your back!

Here’s my summary of the salient points of the book and how they can help you deal with your existing codebase.

First, add tests, then do your changes

The challenge with changing existing code is to preserve the existing behavior.

When code is not tested, how do you know you didn’t break anything?

You need feedback. Automated feedback is the best. Thus, this is the first thing you need to do: write the tests.

Only then you’ll be safe to change the code and refactor.

Your goal is to get there. The point of the book is to show you how you can get there when you have to deal with an impossibly convoluted codebase. Which leads us to the next point…

Adding tests: the Legacy Code dilemma

Before you change code, you should have tests in place. But to put tests in place, you have to change code.

This is the paradox of Legacy Code!

So, how do you go about it? Are you doomed?

You’re not. But you should be extra careful until you got tests in place. You should perform minimal, safe refactorings.

Change as little code as possible to get tests in place.

The recipe is:

- Identify change points (Seams)

- Break dependencies

- Write the tests

- Make your changes

- Refactor

Once you get to the tests, you know how to proceed. The first two points are the difficult ones.

Identify Seams to break your code dependencies

Adding tests on the existing code can be challenging.

Hell, it’s usually a nightmare!

That’s because the code was not written to be testable in the first place. 99% of the time, this is a dependency problem: the code you want to test can’t run because it needs something hard to put in the test.

Sometimes it’s a database connection. Sometimes it’s a call to a third-party server. Sometimes it’s a parameter that’s complex to instantiate. Usually, it’s a complex mix of all that.

To test your code, you need to break these dependencies in the tests.

Therefore, you need to identify Seams.

“A Seam is a place to alter program behavior, without changing the code.”

There are different types of Seams. The gist of it is to identify how you can change the code behavior without touching the source code.

If your language is Object-Oriented, the most common and convenient Seam is an object.

Consider this piece of JavaScript code:

export class DatabaseConnector {

// A lot of code…

connect() {

// Perform some calls to connect to the DB.

}

}Say the connect() method is causing you problems when you try to put code into tests. Well, the whole class is a Seam you can alter.

You can extend this class in tests to prevent it from connecting to an actual DB:

class FakeDatabaseConnector extends DatabaseConnector {

connect() {

// Override the problematic calls to the DB

console.log("Connect to the DB")

}

}There are other kinds of Seams.

If your language allows you to change code behavior without altering the source code, you have an entry point to writing the tests.

Speaking about tests…

Unit tests are fast and reliable

Discussions about testing best practices usually turn into heated debates. Should you apply the Pyramid of Tests principle and write a maximum of unit tests? Or should you embrace the Testing Trophy instead and write mostly integration tests?

Why are people giving contradictory advice?

Because they don’t have the same definition of what a “unit” is. Thus, some people talk about “integration tests” when others talk about “unit tests”.

To avoid any confusion, Michael Feathers gives a clear definition of what is NOT a unit test.

In short, your test is not unit if:

- it doesn’t run fast (< 100ms / test)

- it talks to the Infrastructure (e.g. a database, the network, the file system, environment variables…)

Write a maximum of tests that have these 2 qualities. How you call them doesn’t matter.

Now, sometimes it’s really hard to write such tests because you don’t even understand what the code is supposed to do. There’s a technique for that…

Characterization tests

Before you can refactor the code, you need tests. But writing these tests can be challenging. Especially when code is hard to understand.

“A characterization test is a test that characterizes the actual behavior of a piece of code.”

Instead of writing comprehensive unit tests, you capture the current behavior of the code. You take a snapshot of what it does.

The test ensures that this behavior doesn’t change!

This is very powerful because:

- With most systems, what the code actually does is more important than what it should do.

- You can quickly cover Legacy Code with these tests, giving you a safety net to refactor.

This technique is also called “Approval Testing”, “Snapshot Testing” or “Golden Master” in the wild. Same stuff.

And I also blogged about it: the 3 steps to add tests on Legacy Code when you have short deadlines.

Having short deadlines is a very common situation. When you are in a hurry, it’s hard to take the time not to make things worse. Hopefully, there’s something you can do…

Use Sprout & Wrap techniques to add code when you don’t have time to refactor

Big lumps of code have a gravitational force. They attract more code. If the class is already 2,000 lines-long, who cares that you add 3 more if statements?

Well, you should. Now you have to maintain a 2,010 lines-long class!

But what if you really, really don’t have time to write tests for that class? That’s just 3 if statements and you might not feel like you can justify taking 2 days for that — although you should.

In such a tricky position, you can still make the right call with these 2 techniques.

1. The Sprout technique

- Create your code somewhere else.

- Unit test it.

- Identify where you should call that code from the existing code: the insertion point.

- Call your code from the Legacy Code.

Consider the following example:

class TransactionGate {

// … a lot of code

postEntries(entries) {

for (let entry of entries) {

entry.postDate()

}

// … a lot of code

transactionBundle.getListManager().add(entries)

}

// … a lot of code

}Say you need to deduplicate the entries, but postEntries() is hard to test and you really don’t have time for that.

You can sprout the code somewhere else, like in a new method uniqueEntries().

This new method, you can test easily, because it’s isolated.

Then, insert a call to that method in the existing, non-tested code. Minimal change, minimal risk.

class TransactionGate {

// … a lot of code

uniqueEntries(entries) {

// Some clever logic to dedupe entries, fully tested!

}

postEntries(entries) {

const uniqueEntries = this.uniqueEntries(entries)

for (let entry of uniqueEntries) {

entry.postDate()

}

// … a lot of code

transactionBundle.getListManager().add(uniqueEntries)

}

// … a lot of code

}The diff might be clearer:

class TransactionGate {

// … a lot of code

+ uniqueEntries(entries) {

+ // Some clever logic to dedupe entries, fully tested!

+ }

postEntries(entries) {

+ const uniqueEntries = this.uniqueEntries(entries)

+

+ for (let entry of uniqueEntries) {

- for (let entry of entries) {

entry.postDate()

}

// … a lot of code

+ transactionBundle.getListManager().add(uniqueEntries)

- transactionBundle.getListManager().add(entries)

}

// … a lot of code

}You can Sprout a single method, a whole class or anything that will isolate your new code.

2. The Wrap technique

When the change you need to do should happen before or after the existing code, you can also wrap it.

- Rename the old method you want to wrap.

- Create a new method with the same name and signature as the old method.

- Call the old method from the new method.

- Put the new logic before/after the other method call.

That new logic, you can test.

Why? Because the old method is a Seam you can alter in the tests.

Remember the previous code?

class TransactionGate {

// … a lot of code

postEntries(entries) {

for (let entry of entries) {

entry.postDate()

}

// … a lot of code

transactionBundle.getListManager().add(entries)

}

// … a lot of code

}Another way to tackle the problem would be to wrap it, so we pass to postEntries() the list of deduped entries:

class TransactionGate {

// … a lot of code

postEntries(entries) {

// Some clever logic to retrieve unique entries

this.postEntriesThatAreUnique(uniqueEntries)

}

postEntriesThatAreUnique(entries) {

for (let entry of entries) {

entry.postDate()

}

// … a lot of code

transactionBundle.getListManager().add(entries)

}

// … a lot of code

}In tests, you’d alter the problematic postEntriesThatAreUnique(), so you can test the dedupe logic works.

The diff might be clearer:

class TransactionGate {

// … a lot of code

+ postEntries(entries) {

+ // Some clever logic to retrieve unique entries

+ this.postEntriesThatAreUnique(uniqueEntries)

+ }

+ postEntriesThatAreUnique(entries) {

- postEntries(entries) {

for (let entry of entries) {

entry.postDate()

}

// … a lot of code

transactionBundle.getListManager().add(entries)

}

// … a lot of code

}These techniques are not ideal and they have pitfalls. But they are useful tools to have when addressing Legacy Code.

And when necessary, you can even bend the rules a bit…

Use scratch refactoring to get familiar with the code

When you’ve to work with a code that you didn’t write, that is not tested and that is poorly documented, it’s overwhelming!

Let me remind you of the “how to tackle Legacy Code” recipe:

- Identify change points (Seams)

- Break dependencies

- Write the tests

- Make your changes

- Refactor

So first, you need to break dependencies and write the tests. But where do you even start when code is really opaque?

A good technique is scratch refactoring!

The goal is to get familiar with the code, not to actually clean it.

The only rule is: revert your changes when you’re done.

If you do that, then you can do unsafe changes!

Play with the code as much as you want. Extract functions, simplify code, rename variables… Get to know the code. Once you do, revert your changes and start over with proper tests.

Let’s conclude our review on a cautionary tale…

Don’t make your code depend on libraries’ implementation

“Avoid littering direct calls to library classes in your code. You might think that you’ll never change them, but that can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

I wanted to highlight this advice because it’s a very common mistake. I’ve seen that a lot!

We use libraries to do the job and save us time. So far so good.

But rarely we take the extra time to wrap these tools behind custom abstractions that we own.

Therefore, their implementation leaks across our codebase! All of our code quickly depends on a specific API. It spreads like a parasite. Until someday we easily get rid of it or do a major upgrade of that library.

Think about all the ORM code, monitoring libs, utility packages that you use. Do you control them? Or do you depend on them?

Should you read that book, it still looks old?

Of course, you should.

While I have given you an overview of the advice in the book, there is many more examples and approaches in the book itself!

You have to deal with Legacy Code every day. This is one of the most actionable resources you can find on the topic.

You might have read (or listed) other books such as Clean Code and Refactoring. These are must-reads too. But I’d recommend starting with Working Effectively with Legacy Code.

If you want to refactor your code, you first need to put tests on it. And putting tests on an existing, tangled mess is the point of Michael Feathers’ book.

But the code examples are in Java and C++ and I do python/JavaScript/ruby/…

Granted, you might not feel comfortable with the code examples from the book being written in a language you don’t know.

But that’s OK for 2 reasons:

- Legacy Code is not always easy to read, so that’s actually relevant. It’s a skill you need to practice.

- Java code is object-oriented code that you should be able to understand, even if you don’t know the language.

So, again: this summary gives you a good overview of what kind of advice are in the book. But there are more!

The book goes in detail into how you can apply these advice through different use-cases. If you liked this summary, you’ll enjoy the book.

Aaaaand you’ll love the content I publish every week! 🤠

Subscribe to my newsletter to receive my Legacy Code tips & tricks, directly in your inbox, every Wednesday.

Take care out there!

Written by Nicolas Carlo

who lives and works in Montreal, Canada 🍁

He founded the Software Crafters Montreal

community which cares about building maintainable softwares.

Similar articles that will help you…

7 techniques to regain control of your Legacy codebase

Working with Legacy Code is no fun… unless you know how to approach it and get your changes done, safely.

A quick way to add tests when code has database or HTTP calls

You need to fix a bug, but you can't spend a week on it? Here's a technique to isolate problematic side-effects and write tests within minutes.

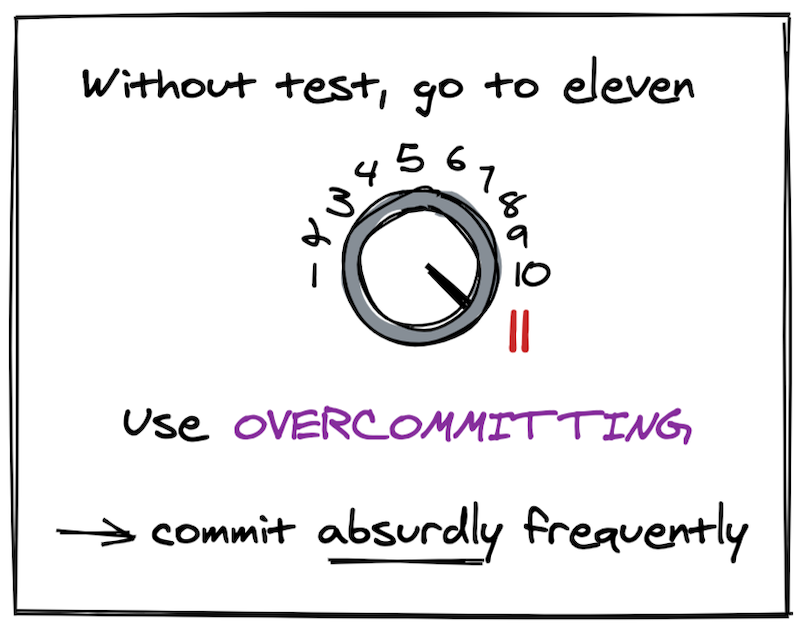

Work faster and safer on untested code with Overcommitting

A technique you can resort to when you need to make risky changes.

How to efficiently practice refactoring katas

How to best learn out of refactoring exercises, depending on your level of experience.