The key points of Refactoring at Scale

⛑️️ My First Aid Kit can help you rescue any codebase quickly and safely!

Refactoring is the process by which we restructure existing code without changing its external behaviour.

If you never got Martin Fowler’s perspective on refactoring code, you will certainly learn a few things from his book. I wrote about that in a dedicated post.

If you are familiar with refactoring, you may also know the feeling of overwhelm that comes with a real-life, large-scale codebase. It’s not only that the scope is huge, but you are not alone: dozens of other engineers are constantly molding it in parallel. How could you hope to improve things and improve code maintainability in this context?

Well, that’s the point of “Refactoring at Scale”.

Maude Lemaire wrote this book based on her own experience at Slack, where she led refactoring projects to keep the cost of adding new features reasonable as they grew.

Coordinating complex changes in a large software project is quite a challenge. And this book gives keys to address that. Let me give you an overview…

Refactoring, but at scale

“At scale” is the issue. When a change affects a substantial part of your codebase, there are too many subtle interactions to anticipate the effects it might have.

Yet, refactoring is particularly valuable to increase developers’ productivity and ease bug detection. Good refactorings make it cheaper to add new features and reduce the risk of introducing regression—thus, you can add more value to your product, faster.

But refactoring is changing the structure of the code. Thus, there is a risk of breaking things. What can help?

- Get faster feedback if something breaks—good automated tests will give you that

- Become more familiar with refactoring moves

Oh and if you don’t have automated tests, Approval Testing will help you quickly set up an anti-regression safety net 😉

When to refactor?

- The scope of the refactoring is identified and small. Just do it.

- The code complexity actively hinders development. Your team spends half of their time fixing regressions? It’s a good moment to pause and discuss refactoring together.

- Product requirements have changed. As you need to implement a new feature, re-evaluate if the system is designed for it. If not, how could you refactor it so the feature is easy to add?

- Performance issues. It’s a great opportunity to push a refactoring project as it can help identify bottlenecks to optimize.

- To keep up with technology. Although Maude is not advocating for being an early adopter, there is a business risk of letting your dependencies rot. You will have to update them at some point… but in a hurry.

When NOT to refactor?

- For fun or boredom. Be mindful of refactoring just for the sake of it, of for “code beauty” and personal taste.

- Because you happened to be passing by. Don’t refactor things that are unrelated to what you are doing. Especially, if you are not familiar with the code. You will create regressions and may make it harder to work with for people who are actively working with it (if any).

- To make code easier to extend… before you know how code needs to evolve. Beware of premature refactoring. If it’s unclear how the product will evolve, it’s better to keep things simple and refactor when you know.

- When you don’t have time. Make sure you have the bandwidth to carry on a large refactoring to the end. Don’t drop it halfway, it may be even worse than the original code.

Planning large-scale refactorings

Is there something your team would like to clean up if they had time? Great. Now let’s start with a plan!

A plan will help you carry on a large-scale refactoring, and can help you convince the stakeholders about such a project. It’s not just a vague complaint about code quality anymore.

Maude suggests the following steps:

- Define your end-state. What would “done” look like? Aim for “better than today” rather than “in a perfect world”.

- Map the shortest path to get there.

- Write down every step you can come up with. Put that draft aside. Come back a few hours later to re-order the steps in chronological order.

- Gather coworkers interested in contributing and brainstorm together.

- Identify strategic milestones. For each step, ask yourself:

- Is the step valuable on its own?

- Does this step feel attainable in a reasonable time frame?

- If something comes up, could we stop at this step and pick it back up easily after?

- Give rough estimates for each milestone. Yes, we suck at estimating. But stakeholders will ask for one. Hopefully, we do better at estimating things relative to each other.

- Assign a number from 1 to 10 (1 is short, 10 is long).

- Estimate how long your lengthiest milestone might take. Imagine what’s most likely to go wrong during that milestone. Don’t overdo it, but add a reasonable buffer.

- Measure each shorter milestone against the lengthier one.

- Determine metrics to track progress for each milestone. So you can tell that you are moving, which is important for morale when you are deep in refactoring 😄

Here’s an example of what a plan would look like, from Maude:

# Unify backend repositories

## Create a single requirements.txt file

- **Metric:** Number of distinct lists of dependencies.

- Start = 3

- Goal = 1

- **Estimate:** 2-3 weeks

- [] Enumerate all packages used across each repositories

- [] Audit all packages and narrow down the list to only required packages with corresponding versions

- [] Identify which version each package should be upgraded to in Python 2.7

## Merge all the repositories into a single repository

- **Metric:** Number of distinct repositories.

- Start = 3

- Goal = 1

- **Estimate:** 2-3 weeks

- [] Create a new repository

- [] For each repository, add to the new repository using git submodules

## Build a Docker image with all the required packages

- **Metric:** Number of environments using new Docker image.

- Start = 0

- Goal = 5

- **Estimate:** 1-2 weeks

- [] Test the Docker image on each of the environments

## Enable linting through continuous integration for the monorepo

- **Metric:** Number of linter warnings.

- Start = ~15,000

- Goal = 0

- **Estimate:** 1-1.5 months

- [] Choose a linter and corresponding configuration

- [] Integrate the linter into continuous integration

- [] Use the linter to identify logical problems in the code

## Install and roll out Python 2.7.1 on all environments

- **Metric:** Number of jobs running on Python 2.7.1 with new _requirements.txt_ file.

- Start = 0

- Goal = 158

- **Estimate:** 2-2.5 months

- [] Locate tests for each repository; determine which tests are reliable

- [] Use Python 2.7 on a subset of low-risk scripts

- [] Roll out Python 2.7 to all scriptsBeware of scope creep. It’s very easy and tempting to “do that while we are at it”. You are more likely to succeed if you keep a sharp focus. Postpone that suggestion until after the refactoring is complete. Chances are the refactoring will make such change easier to do.

Getting buy-in from your manager

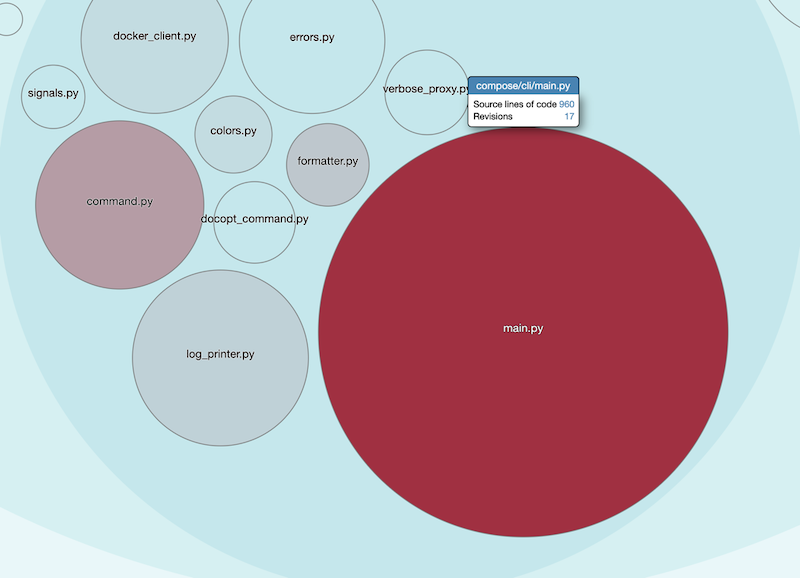

This may be tough. I already wrote about arguments that may work and how you can use git logs to build a case for such a project.

After all, why can’t the company keep handling this tech debt like it’s already doing? What’s the value for the customer? How would they convince their own manager about it?

Maude shares a few tips to help you with these discussions:

- Figure out when you believe the team should begin work on the refactor, and why it’s an optimal time.

- Kick off the conversation during a one-on-one.

- Pinpoint what your manager is most concerned about, and address these points.

- Bring up counter-arguments for them, to demonstrate that you have weights pros and cons.

- Look for external opinions and tell your manager about them. E.g. get your teammates on the same page. Together, you can have more impact.

- If you can’t get buy-in on something that causes you to do unrewarded maintenance work, stop doing it. Stop protecting the company from the consequences, so the problem is clearer, and stop being on your shoulders.

In my experience, this is not just about legacy code, but about legacy culture. If you are in a position of leadership, you can foster these initiatives by making refactoring work visible. For instance:

- Mention refactoring efforts during internal Sprint demos.

- Give kudos to the people who upgraded the dependencies.

- Work with HR to reward code maintenance.

Building the right team

Maude gives a lot of advice about setting up a team which would address a large-scale refactoring project.

What resonated the most with me are:

- If your only option is to execute a large, cross-functional refactor alone, consider not doing it at all. You can’t work against the stream.

- Make sure to keep the momentum of the project until the finish line. If your team is losing motivation, find ways to boost it early before inertia kicks in. Cross the finish line.

- Build a team with a handful of active contributors and experts. Experts may not be involved, but are available for discussions in a timely manner.

- When refactoring overlaps multiple teams, have your team help others do the work. Preparing tests, documenting the process, and providing codemods are good options. In particular, make a case for the benefits of the refactoring from the other team’s perspective.

Executing a large-scale refactoring

If your team is not already communicating effectively on a frequent basis, maybe you should consider delaying a large refactoring project.

— Maude Lemaire, “Refactoring at Scale”

Communication is key.

Especially at scale. Your team is connected to others through the codebase you are evolving. Changes can have unexpected consequences. Agendas may conflict.

There are things you can do to help your team succeed in such a project:

- Identify a place to collect all documentation related to the project. It should clarify what’s the plan, the current status, and other technical details that could be helpful to stakeholders.

- Communicate early and often to other stakeholders. Redirect them to that single source of truth.

- Clarify where people can ask questions.

It’s also a good idea to encourage knowledge sharing within your team.

Pairing is one way to do it. Encourage it, but don’t make it mandatory—make them feel the benefits of pairing, don’t force it upon them.

Rollout strategies: dark vs. light mode

Maude reports that she had good success with what was known at Slack as “Dark Mode” and “Light Mode” rollouts.

The idea is to deliver large-scale changes in the following steps:

- Dark Mode. Call both the old and new implementations together. Compare the results and return the ones from the old implementation. It’s a good way to exercise your refactoring with production data, without impacting the app behaviour much. If you are concerned about performance, you may sample the new implementation of a % of requests.

- Light Mode. Call both the old and new implementations, compare the results, but return the ones from the new implementation now! The old implementation is still here, so you can revert easily if needed.

- Finally, sunset the old implementation by removing unused code and data.

This allows you to collect feedback as soon as possible. This feedback will help you adjust to reality—no plan can prepare you for that. As your confidence increases, you progressively roll it out.

The downside is that the codebase will be in an intermediate state for a while. But that’s what it is with large-scale refactorings.

Just make sure to push the project across the finish line. Don’t let both implementations live forever in the code.

Cleanup your feature flags 😉

Conclusion

There are many details that I haven’t mentioned here. You can tell Maude Lemaire knows about her topic and sprinkles tons of excellent advice that can resonate with you throughout the book.

Should you fix a bug that you come across? How would you make your refactor stick? How do you manage the shortcuts you may take during the refactoring? Etc.

The last part of the book is dedicated to 2 concrete use cases. Two stories from the trenches at Slack, where Maude shares what went well… and what didn’t:

- How they cleaned up redundant database schemas that were causing a lot of headaches and performance issues. The trick was to do so while other teams were actively developing on top of it. Of course, there were no tests. Hint: feature flags and exhaustive monitoring are precious.

- How they migrated to a new database so they could scale and accommodate new important features. Spoiler: this refactoring took twice the time they initially estimated. It was tricky, yet it seems they were able to roll it out until completeness.

So yeah, “Refactoring at Scale” is a book I would recommend. It’s rooted in the reality of growing companies that need to go fast while having a legacy to carry on. Both a blessing and a challenge. If that’s your reality, then you will get the most from this book 👍

Written by Nicolas Carlo

who lives and works in Montreal, Canada 🍁

He founded the Software Crafters Montreal

community which cares about building maintainable softwares.

Similar articles that will help you…

The key points of Re-Engineering Legacy Software

Here's an interesting book on approaching Legacy Software. Here's my summary of its salient points.

Delete unused code (and how to retrieve it)

Dead code adds noise to the codebase and should be deleted. Yet, deleted code feels harder to retrieve. Here's how to find such code easily with git!

Convince managers to address Tech Debt with Enclosure Diagrams

How to come up with a plan that will resonate with non-technical people, in 7 concrete steps.

The key points of The Legacy Code Programmer's Toolbox

This book is full of tips to get into an unfamiliar codebase. Here's my summary of its salient points.