Refactoring vs. Defactoring

⛑️️ My First Aid Kit can help you rescue any codebase quickly and safely!

“Refactoring” is an abused word, in my experience.

When most developers talk about “refactoring the code”, they really mean “restructuring the code”. Rewriting it. Certainly to make it better and fix some bugs. That will be a mix of re-organizing the code, changing the modeling, and modifying some behavior along the way—for the best!

That’s not what I mean.

When I say “refactoring”, I’m referring to Martin Fowler’s definition of it:

Refactoring (noun): a change made to the internal structure of software to make it easier to understand and cheaper to modify without changing its observable behavior.

Fixing a bug is not refactoring. Adding a new feature is not refactoring. But we may refactor before we fix a bug or add a feature.

Actually, it’s a good idea to do so.

It’s also a good idea to keep these 2 phases distinct.

Don’t mix refactorings & behavior changes.

In a recent post, Jason Swett shared this very advice: don’t mix refactorings with behavior changes.

Jason explains why it’s a problem to mix these:

- It adds risk to break something without realizing it.

- It’s harder to find what change created a bug.

- It makes code harder to review.

Instead, he recommends refactoring code in a new branch and getting this branch merged into the main one, so you can get this back in your feature/bugfix branch.

I think that’s good advice overall.

In my experience, there are other things that can help:

- Distinct commits that contain refactorings from commits that introduce changes, even without creating a branch.

- Commit more frequently, so 1) is easier to do.

- Prefix your commit message with

Rfor refactoring andCfor the other kind of changes. It makes it easier to review the code. That’s my lightweight version of Arlo’s commit notation. - Learn and use automated refactorings. Some IDEs provide that out of the box. Others have extensions. Automated refactorings are fast and safe—even when you don’t have tests. Refactor one thing > commit. Move on.

I think this is more than a technique. It’s a mindset.

It has changed the way I code just like learning git did. I wasn’t aware you could work like that before. It took some time and practice until I finally understood it. Now, it just feels natural. It makes my work much safer and simpler. I am more aware of what’s going on, so I can put my best quality into my work. 🏆

Think about it as wearing 2 different hats:

- With the Refactoring hat 🎩, you are not allowed to change the way the code works.

- With the Change hat 🧢, you can change code behavior, but you try to minimize that change.

When you work on the code, you would constantly switch between these two. But you would be aware of doing that.

So you want to fix a bug. But you see some badly named variable here. You put your Refactoring hat 🎩 on and you rename the variable. Commit. Done.

Then, you put your Change hat 🧢 on to add the missing fallback value where it should be. While doing so, you realize this code would be easier to read if it uses a guard clause instead of being nested. STOP!

You are wearing the Change hat 🧢, so you shouldn’t be refactoring.

You actually have two options:

- Commit the change. Put the Refactoring hat 🎩 on and use a guard clause. Commit again.

- Revert the change. Put the Refactoring hat 🎩 on and refactor the code. Commit. Put the Change hat 🧢 on and do the change on the transformed code.

In this case, I would probably do 1). In other scenarios, I would do 2).

You may do a lot of 2) and ship an intermediate Pull Request with all of these refactorings. They aren’t supposed to change code behavior, so they are easy to review. They also make it easier to make my actual change later!

Or maybe you would ship both the refactorings and the code change in the same PR. That is fine if they are in different commits—ideally, refactoring commits first.

The actual change is small, therefore it is easier to review.

What matters is really to distinct refactoring moves from the rest of the changes.

Defactoring

There is a particular kind of refactoring I would like to focus on: Inlines.

Inline Variable for instance. That is a refactoring move. The code will behave the same, whether or not the variable is extracted or inlined (and duplicated).

If you think about it, Inline Variable is the reverse operation of Extract Variable. Extracting variables is a common move we do to reduce duplication, increase abstraction, and overall make the code easier to read.

So why on Earth would you want to Inline Variable? 🤨

That’s an interesting question. While some editors have automated the Extract Variable refactoring, most of them won’t inline things for you. It feels like second-class refactoring. And yet, I think it’s a core one.

There are different reasons why you would inline a variable:

- The variable name doesn’t tell you more than the expression itself. In this case, the variable adds unnecessary indirection. Inlining reduces the cognitive complexity (less moving parts).

- The variable gets in the way of another refactoring. This happens when previous abstractions aren’t the best anymore, and you want to go another way.

I find myself using this refactoring often to remove a temporary variable that has no more use. For instance:

function addParens(value) {

const string = `(${value})`

return string

}The string intermediate variable doesn’t add much value. We fall into scenario #1. I would inline this to get rid of the noise:

function addParens(value) {

return `(${value})`

}Think about Inlining as a defactoring.

I defactor a lot when I work with Legacy Code. I temporarily inline things to get a better understanding of what the code is doing. Then, I revert. Or maybe I extract things differently.

Defactoring is a cognitive refactoring. Making the code less abstract can help you process what’s going on. There are fewer things to hold in your brain. Less scrolling back and forth. Some abstractions aren’t necessary anymore, like this temporary variable above. Getting rid of the indirection can make the code easier to maintain.

Defactoring is also a common move before refactoring the code differently. Old abstractions may not be good enough anymore. Requirements change all the time, and we should adapt the code constantly.

In this post, Jimmy Bogard illustrates how you would defactor to prepare for extracting domain code.

Refactoring

At the end of the day, good abstractions are a matter of balance. It takes practice and experience to find the sweet spots that will make your code easier to maintain.

If you want to go down that path, I have a few recommendations for you.

Learn what your editor can automate for you. Some IDE like Jetbrains ones (ReSharper, Webstorm, PHPStorm…) can do a lot! Others like VS Code have extensions to help you do so—if you are doing JS/TS with VS Code, you should have a look at Abracadabra.

For what can not be automated, learn the moves. Martin Fowler’s Refactoring book is the reference.

If you are looking for something more interactive, Refactoring Guru can be useful in my opinion. I like that their catalog has public code examples. A nice complement to Fowler’s book.

This topic is so interesting that I’m working on a course myself. My goal is to teach JavaScript developers to refactor legacy codebases safely. Unlike a book, the course will be interactive—I learn better when I do things, and I know I’m not the only one 😉

I’m also leveraging my own experience to build a learning path that makes sense for JS devs: start with the common ones, then learn more complex moves that require mastering the basics, etc.

If that is something you are interested in, let me know. I will give you some updates when I have more details.

In any case, practice your refactoring skills on these 5 coding exercises. They are tailored for working with Legacy Code!

What is your own experience with Refactoring? Are you used to switching hats? 🍻

Written by Nicolas Carlo

who lives and works in Montreal, Canada 🍁

He founded the Software Crafters Montreal

community which cares about building maintainable softwares.

Similar articles that will help you…

3 must-watch talks on Legacy Code

I have hosted more than 37 speakers to talk about Legacy Code tips and tricks. Here is my top 3 of the talks you should probably watch!

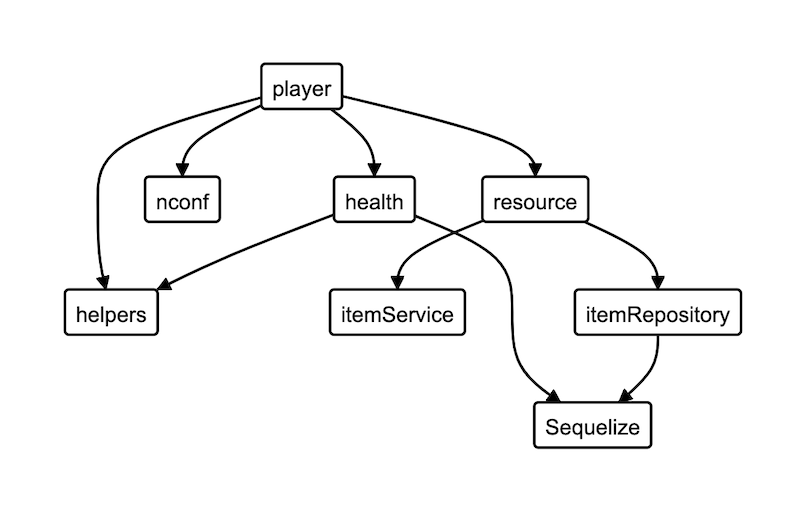

Safely restructure your codebase with Dependency Graphs

Even drawing them by hand can help you make sense of a tangled codebase! Let's see how they can help, and what tools you can use to generate these.

Technical Debt, Rewrites, and Refactoring

5 great talks on Legacy Code that I had the pleasure to host. Learn how to prioritize Tech Debt and rewrite systems incrementally.

5 coding exercises to practice refactoring Legacy Code

Feeling overwhelmed by your legacy codebase? These katas will help you learn how to tackle it.