It's like coding in the dark!

⛑️️ My First Aid Kit can help you rescue any codebase quickly and safely!

I like reading different studies about developers and how they interact with unfamiliar codebases at work.

Here, I would like to share one that I found particularly insightful… and painfully close to my own experience. The title:

“It’s Like Coding in the Dark”: The need for learning cultures within coding teams

— Catherine Hicks, Catharsis Consulting (2022) PDF source

The study got 25 code writers from diverse backgrounds to work on a debugging task and interviewed about their experience of onboarding an unfamiliar, collaborative codebase.

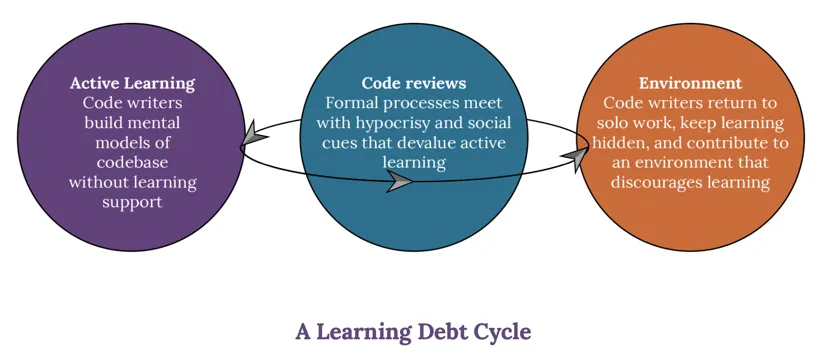

Active Learning is invisible work

For all participants, working on existing code meant they had to spend time actively learning how things work. Typically, they would break things to test assumptions, clarify implicit knowledge, identify anchor points for understanding, etc. This is not a surprise and a topic I wrote extensively about myself. The goal is to build a mental model of how the code is working to decide how it should be changed.

However, this active learning phase is invisible work. In most companies, it’s not recognized as part of the individual performance evaluation. Although necessary for anyone getting into code they are not familiar with (or have forgotten about), getting up-to-speed is not perceived as actual work.

Therefore, code writers won’t invest time into making this process easier for the next person. They may have spent 3 days learning how to run the backend on their local machine. Once it’s working, they won’t spend more time documenting the missing bits or automating the process, because it’s not what is rewarded.

Code writers’ “failures” to document or transfer knowledge were not driven by laziness or lack of care. Rather, [environmental pressures] pushed them to navigate complex tensions between performance and learning goals. And when making learning visible does not feel safe, performance culture wins.

This contributes to the problem, and each individual just has to “figure it out” by themselves.

This is something I’ve witnessed a few times when struggling with the existing code is perceived as part of the onboarding:

Lack of documentation, frustration with invisible decisions, and lack of mentorship for junior teammates were frequently treated like rites of passage, perhaps even the inevitable consequence of high-quality code work.

If you are looking for solutions to this specifically, I would recommend Dr. Felienne Hermans’s work on “The Programmer’s Brain”. I summarized some of it in this article:

- Prepare flashcards for the newcomer to teach the important concepts of your system

- Ask the new developer to implement a certain method, giving clear instructions on what it should do

- Or get them to just explore a part of the codebase to get a general sense of how it works

- Maybe have them summarize a part of the codebase, some class, in natural language

- Read some code together and ask them to summarize what they understood.

- Pair on implementing the next feature together.

Code Reviews don’t feel safe

When it comes to submitting code changes, most code writers are afraid of disclosing too much information.

Have you ever been defensive when getting your code reviewed by your peers? You are not alone!

Code reviews generally turn out to illustrate the conflict between the work that needs to be done, and the personal reputation of the developers. Here, the 3 lines of code produced matter more than the two days it took to understand why there is no need for more.

Interestingly, even in environments where people talk about ideals regarding collaboration (eg. pairing, automated tests, documentation), what actually happens may differ. New developers will look at what other developers do to interpret what is acceptable.

The fear of “not looking like an engineer” often wins over the inner beliefs of quality software development. Instead of opening a draft pull request to discuss some ideas, engineers will resort to going for a solution that seems acceptable and justify their code output during the review.

After review, everyone gets back to solo work

“It’s like coding in the dark. Every once in a while someone comes in to turn on the lights and stare at you, like review, but then you feel like you have to defend something. But mostly I feel like I’m just sitting here with all the lights off.”

Does that sound accurate to you? It does look like a lot of places and cultures I’ve worked with, regardless of the quality of the code.

This tension between learning and performance leads to loneliness. Code writers feel like individuals working in silos to produce visible performance work while letting the culture of learning and sharing degrade.

This is what the author calls The Learning Debt.

There is hope

Although sometimes depressing, I find these sorts of studies to be precious as they put words on what would just be a hunch.

In particular, they provide ideas on what we can do to turn the ship around:

- Involve people in defining how their “success” is measured instead of imposing it on them.

- Make time and space for learning and sharing knowledge. For instance, introducing dailies at work can help.

- Make documentation “count” and give time to developers for collaboration.

- Celebrate sharing collaborative support and proactive problem-solving. Don’t just reward the firefighters, but acknowledge the ones who are preventing fires in the first place.

- Find ways to highlight the impact of learning debt on the team/company.

If you want to spread the word around, I recommend checking out this talk that is based on the study:

Written by Nicolas Carlo

who lives and works in Montreal, Canada 🍁

He founded the Software Crafters Montreal

community which cares about building maintainable softwares.

Similar articles that will help you…

The Legacy Code Survival Guide: Add Features Without Fear

Steven Diamante gave a great presentation on Legacy Code at the Seattle Crafter meetup. Let's dive into it!

The key points of The Legacy Code Programmer's Toolbox

This book is full of tips to get into an unfamiliar codebase. Here's my summary of its salient points.

7 advice to help you inherit a legacy codebase

My recap of the most common and useful advice one can give to tackle Legacy codebases.

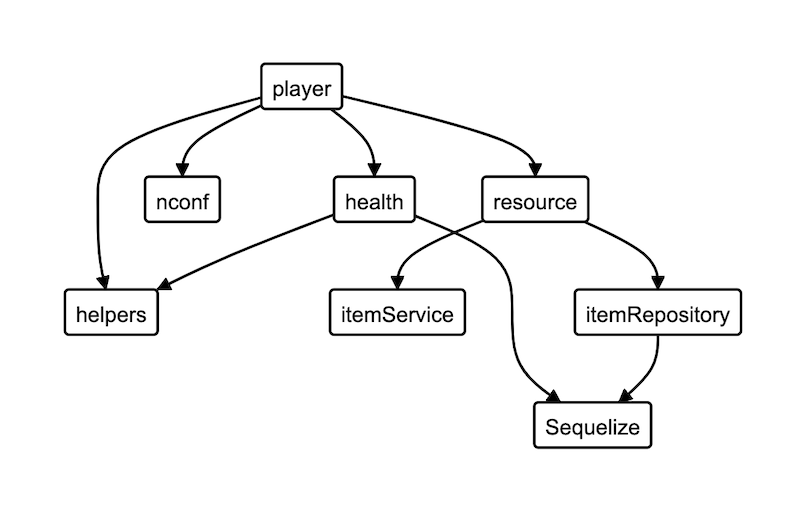

Safely restructure your codebase with Dependency Graphs

Even drawing them by hand can help you make sense of a tangled codebase! Let's see how they can help, and what tools you can use to generate these.